A prehistoric culture from mainland Greece, now called the Mycenaeans, inherited the fabulous brilliance of Minoan Crete. When the Bronze Age collapsed, all signs of state-level society disappeared from Greece, and both Minoans and Mycenaeans disappeared from history. Only their oral tales remained, composed half a millennium later by Homer into the Iliad and the Odyssey, and these have stood ever since like colossi dominating Western literature. Yet most scholars came to assume that Homeric tales and even the society they described largely were fiction. Then a few romantically-minded 19th-century amateur archaeologists (most memorably Heinrich Schliemann) took those tales seriously and those brilliant predecessors of the ancient Greeks exploded from obscurity. Humanities West is delighted to bring the Mycenaeans to you, including the archaeologists who uncovered the latest Mycenaean finds (2017), as this still-young archaeological field continues to deepen our understanding of our Western Civilization.

FRIDAY, MAY 3, 2019 | 7:30 – 9:30 pm

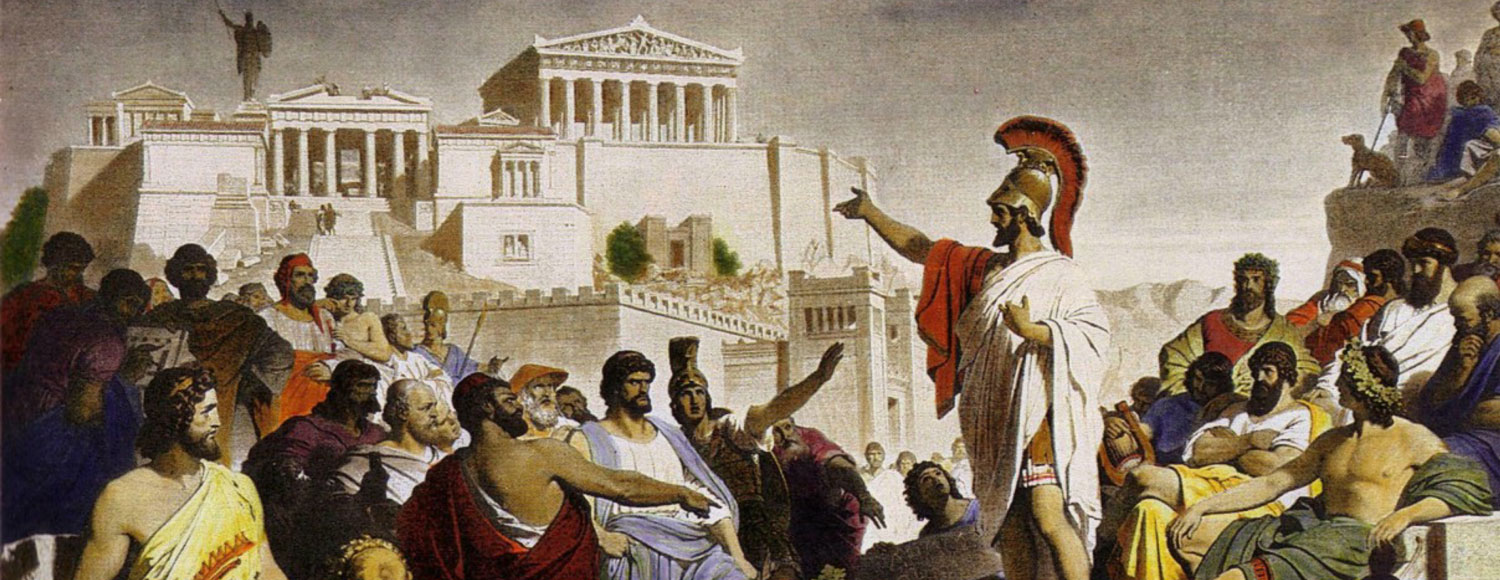

Once Homer Was Enough / Douglas Kenning (Sicily Tour). Western Civilization once knew the Late Bronze Age Aegean only through the Homeric tales. Yet these were stories adrift from history; archaeology caught up with Homer barely a century ago. For twenty-six centuries before that, Homer stood like a colossus over Western culture, even as educated opinion generally denied that the civilization he sang of actually had existed. Let us stand a moment in this beautiful innocence, when myth was our only window on the Late Bronze Age Aegean. We’ll begin with the mythic backstory (e.g. the Judgment of Paris), follow the storyline through the Iliad and Odyssey, and finish with a mention of other Mycenaean-derived myths, those connected to the Iliad story (e.g. Trojan Horse, the Oresteia) and those not (e.g. Perseus, Theseus, Bellerophon and Pegasus). We’ll illustrate the stories as Western civilization always has, with great art, and suggest what they might tell us about the historical Mycenaeans.

Lecture / Performance / Demonstration: Mycenaean Literature, Music, and Performance Culture – What Do We Know? What Can We Reconstruct? / Mark Griffith (Classics, UC Berkeley). No literary or musical texts survive from the Bronze Age Greeks; but our steadily-growing knowledge of several of their neighbors’ literatures and musical performance traditions, along with vital clues preserved within the poems of Homer and Hesiod, enables us to recreate—or to surmise with some degree of confidence—key elements of the song-types, dances, instrumental tunings, and epic stories about gods and heroes that they adopted from and shared with those neighbors. This lecture will explore the rich visual, documentary, and literary evidence recovered from Bronze Age Anatolia (Hittites, Luwians / Trojans, and others), from Crete, and from the Levant (especially Ugarit) that can help us to fill in some of the missing pieces of Mycenaean performance culture.

SATURDAY, MAY 4, 2019 | 10 am – 4 pm

Bronze Age Myth Morphs into History / Ian Morris (Classics, Stanford). Archaeology discovers a people we’ve been reading about for 2,700 years but didn’t know existed. Legend and story become real as archaeology rises to claim authority away from literature in deciding matters of the past, a story that includes Schliemann, Evans, Blegan, and the rest. Standing now on archaeology and history, what do we know about the late Bronze Age context given archeological finds in Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Asia Minor? Who were the Minoans? How and why did they give way to the Mycenaeans? Why and how did the Mycenaeans rise to regional dominance?

The Griffin Warrior of Pylos, Bronze Age Archaeology, and Homer Today / Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker (co-presenting) (Archeology, University of Cincinnati). University of Cincinnati excavations at Pylos resumed in 2015 after Carl Blegen, discoverer of the Palace of Nestor, suspended his campaigns in 1969. Blegen and other 20th-century archaeologists shaped the field of Greek prehistory after Schliemann’s discoveries at Mycenae in the 1880s. Our reexamination of Blegen’s finds produced new results reminiscent of practices described in Homer’s Odyssey, including evidence for burnt animal sacrifice. Finds from new excavations shed light on the 15th century BCE, when the Mycenaean civilization was being created on the Greek mainland. The 2015 discovery of the grave of the so-called “Griffin Warrior,” along with four gold rings, is of great significance for the study of Minoan and Mycenaean ideology. This unique, undisturbed burial affords an unparalleled opportunity to examine Early Mycenaean funerary ritual, gender association with grave goods, and burial structure. Other discoveries from this grave suggest that myths and legends of the sort incorporated in the Homeric poems were already in circulation at the dawn of the Mycenaean civilization.

Daily Life at Mycenae: Work, Worship, and the Wanax / Kim Shelton (Classics, UC Berkeley). This talk explores life at a Mycenaean palatial center during the Late Bronze Age that highlights the everyday experiences of a bustling, energetic world with monumental architecture, large-scale craft production, and religious ritual. What is Mycenaean culture and how is it discovered through archaeological excavation at the site? The Late Helladic culture developed from a combination of traditional Greek characteristics and contact with the Minoan culture on Crete. A complex palatial state formed out of this that is accessed through their settlement and mortuary architecture, their arts and crafts, many of which were traded on an international scale, and through a fragmentary textual record. We will discuss the potential daily activities and responsibilities of the people at Mycenae, whether King Agamemnon or Joe Mycenaean.

Mycenaeans North and South: Beyond the World of the Palaces / Sarah P. Morris (Classics and Archaeology, UCLA). Recent research has greatly enriched the material record of the Bronze Age in northern Greece, especially in Thessaly (once the northern “boundary” of the Mycenaean world) and Macedonia. Greek myth enriches these regions with the story of Jason and the Argonauts in Thessaly, and of the Homeric hero, Philoktetes, associated with a northern kingdom and his exile on the island of Lemnos. A key feature of this Mycenaean “periphery” is the survival of Bronze Age communities long after the southern Greek collapse, perhaps in part as a result of their very distance from palatial powers. Since the Neolithic, northern Greece engaged with networks spanning the Balkans and the Aegean, linking inland resources with maritime trade via powerful riverways, in a lively north-south traffic in precious metals, timber, and amber. This gives the area a head start on the Bronze Age, and the resilience to survive past its end of the second millennium B.C. New excavations trace a growing picture of this trans-Mycenaean Bronze Age in the north Aegean, where signs of contact with southern Greece long outlast the palatial era to shape post-Mycenaean identities and memories.

Panel Discussion with the presenters.