Marines’ Memorial Theatre, San Francisco

The fall of the Roman Empire is often seen as a major dividing line in European history, but its offshoot, the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire, lived on from 330 to 1453, providing continuity as a fascinating cultural and political power. In fact, the Byzantines thought of themselves as Romans, while imposing a predominantly Greek culture and Eastern Orthodox religion over their multiethnic territories, dominating the eastern Mediterranean, Southern Italy, the Balkans, and North Africa. The Byzantine Empire bridged east and west, ancient and modern, until overwhelmed by the rising power of the Ottoman Turks.

Presented in collaboration with the Consul General of Greece in San Francisco.

Friday, February 28, 7:30 to 9:45 pm

Performance: Peter Kalafatis and the Belmont Dancing Group Enomenoi

Performance: Anthology of Byzantine Melodies. Reverends Apostolos Koufallakis, Nikos Bekris, John Kololas, Dimosthenis Paraskevaidis, Nebojsa Pantic, Michael Prevas, Alex Leong, Peter Salmas, Jon Magoulias, and Aris Metrakos; and George Haris and Basil Crow perform under the direction of Costas Haralambopoulos (Annunciation Cathedral, San Francisco)

Byzantium as a World Civilization. Maria Mavroudi (UC Berkeley). Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century scholars assigned Byzantium a marginal role in the development of world civilization, one limited to the preservation of “classical” Greek texts. However, the Greek texts chosen for translation into Latin and Arabic during the medieval period indicate that Byzantium’s contemporaries were not primarily interested in its pagan Greek heritage but in its Christian and Roman traditions, especially since the Byzantine state viewed itself (and was also viewed by its Eastern neighbors) as the continuation of the Roman empire. Consequently, they chose to translate a great number of biblical, patristic, hagiographical, liturgical, and legal texts, while the Arabic and Latin translations of pagan Greek texts were influenced by Byzantium’s monotheistic understanding of their content. We also have Byzantine translations of medieval Latin and Arabic texts. This suggests that the Greek, Latin, and Arabic Middle Ages were all interested in the same larger philosophical and scientific questions and occasionally exchanged ideas on them.

Saturday, March 1, 10 am to noon and 1:30 to 4:00 pm

Constantinople – the New Rome in Late Antiquity. Rossitza Schroeder (Pacific School of Religion, Berkeley). The city of Constantinople was named New Rome or Second Rome very soon after its foundation in AD 324; over the next two hundred years it replaced the original Rome as the greatest city of the Mediterranean. How did perceptions of Rome and Constantinople change? Who were the new emperors and how did they live in their new capital? What role did the New Rome’s new religion, Christianity, play?

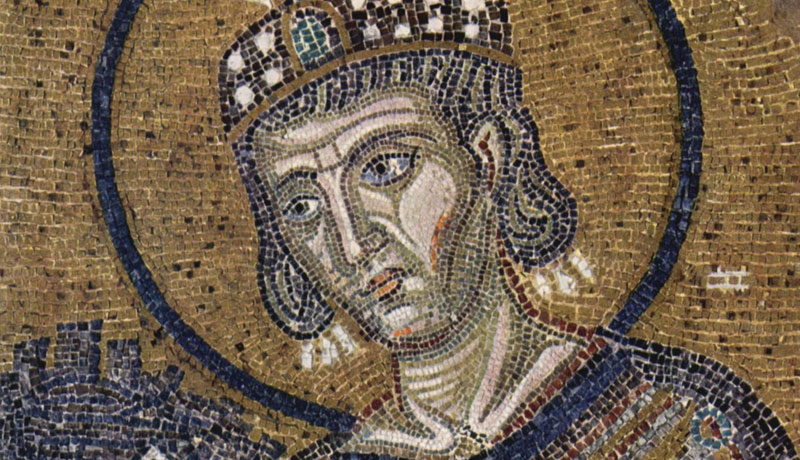

The Many Faces of Byzantium: Ideologies of Power from Constantine to Mehmed the Conqueror. Dimiter Angelov (University of Birmingham, UK and Harvard). The Byzantine Empire (330-1453) was the direct successor to imperial Rome in the eastern Mediterranean—a flourishing civilization that received, preserved, and reinterpreted many of the political and intellectual traditions of antiquity. What was the political ideology of Byzantium throughout its millennial existence? How was it constructed, communicated, and questioned throughout the centuries? The original voices of Byzantine thinkers and the powerful images produced by Byzantine artists will help to answer these and other questions, bringing to life a rich world of politics, imagination, and continual change and rediscovery of the past.

Performance: Holy Trinity Youth Choir, with Anysia Dumont

Hagia Sophia and Multi-Sensory Aesthetics. Bissera Pentcheva (Stanford). Focusing on the 6th-century interior of the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, Professor Pentcheva explores the optical shimmer of marble and gold and its psychological effect on the spectator as recorded in Byzantine ekphrasis and liturgical texts. In turn, this optical shimmer, marmarygma in Greek, is linked to the acoustic properties of marble, especially its capacity to reflect sound waves. The meaning of the optical and acoustic reflection is related to the Eucharist rite and more specifically to the concept of animation, empsychosis. The exploration of acoustics is further deepened by the use of the sound of exploding balloons and modern digital technology to measure the reverberation time of the interior and to generate with its aid computer auralizations of Byzantine chant, recorded anechoically (with minimal room acoustics). Combining literary analysis, philological inquiry, and scientific research, this study uncovers the multi-sensory aesthetics of Hagia Sophia and recuperates the notion of aural architecture.

Constantinople and the Generation of Orthodox Painting, Sharon E. J. Gerstel (UCLA). The legacy of Byzantium can be traced in the remains of thousands of painted churches that still stand and serve for common worship. Looking at the remains of monumental decoration in the Byzantine capital, both painted and mosaic, can one characterize an art form that was uniquely metropolitan? What was the role of the capital in the creation and dissemination of artistic styles and subjects? Professor Gerstel looks at the last and most famous phase of ecclesiastical decoration in the Byzantine capital (1261-1453), and its echoes in other regions of the empire.

Panel Discussion with Presenters Moderated by George Hammond (Humanities West)

Presenters

Dimiter Angelov is Professor of Byzantine History, Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham, UK, and Visiting Associate Professor, Harvard. His research and teaching interests lie in the intellectual, political and institutional history of the Byzantine Empire, with a particular focus on the 13th-15th centuries. His book on imperial ideology and political thought in Byzantium (1204-1330) (2007) examined little known texts in order to shed light on the political imagination of the Byzantines, who saw their empire being transformed into a second-rate power in the Eastern Mediterranean. He is currently working on a monograph on the Byzantine crown prince, emperor and philosopher Theodore II Laskaris (1221/22-1258); the study makes use of the analytical and discursive potential of historical biography to open up a broader vista on the transformation of Byzantine culture after the fall of Constantinople in 1204.

The Enomenoi Dancers are from the Church Of The Holy Cross in Belmont. Enomenoi is directed by Peter Kalafatis. Peter has been involved with Greek dancing for over 38 years – performing with several Greek Folk Dance groups all over the West Coast. For the last several years he has been able to pass on his love of Greek dancing by directing the Enomenoi Dance Group. Enomenoi has been invited to perform at venues all across the state of California, as well as Nevada. Enomenoi has participated in the annual Greek Folk Dance Festival, and has won multiple awards for their performances.

Sharon E. J. Gerstel is Professor of Byzantine Art History and Archaeology, UCLA. Trained in art history and religious studies, Gerstel’s work focuses on the intersection of ritual and art, particularly monumental painting. Selected publications include Beholding the Sacred Mysteries (1999); A Lost Art Rediscovered: The Architectural Ceramics of Byzantium (with J. Lauffenburger) (2001), Thresholds of the Sacred: Art Historical, Archaeological, Liturgical and Theological Views on Religious Screens, East and West (2007), and Viewing the Morea: Land and People in the Late Medieval Peloponnese (2013). Awards include a membership at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, and a J. Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2011-2012 to complete Landscapes of the Village: The Devotional Life and Setting of the Late Byzantine Peasant (forthcoming Cambridge). She has also published numerous articles on Byzantine women, including empresses, village widows, and rural nuns.

Maria Mavroudi is Professor of Byzantine History, UC Berkeley (PhD, Byzantine Studies, Harvard; MA, Byzantine Literature, Harvard; BA, Philology, University of Thessaloniki, Greece). Her research interests include Byzantium and the Arabs; bilinguals in the Middle Ages; Byzantine and Islamic science; the recycling of the ancient tradition between Byzantium and Islam; Byzantine intellectual history; and the survival and transformation of Byzantine culture after 1453. Selected publications includeThe Occult Sciences in Byzantium, ed. with Paul Magdalino (2007); A Byzantine Book on Dream Interpretation: The Oneirocriticon of Achmet and Its Arabic Sources (2002); Artemidorou Oneirocritica. Translation of a 2nd century A.D. manual on dream interpretation from Classical into Modern Greek and Introduction (2002). Her numerous honors and awards include a MacArthur Fellowship (2004-09), fellowships at Princeton and Dumbarton Oaks, and a Whiting Fellowship in the Humanities for Dissertation Completion.

Bissera Pentcheva is Associate Professor, Art & Art History, Stanford (PhD Harvard). Her work focuses on aesthetics and phenomenology of Byzantine Art. Publications include The Sensual Icon: Space, Ritual, and the Senses in Byzantium (2010), and Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium(2006), awarded the John Nicholas Brown Prize 2010 of the Medieval Academy of America for an outstanding first monograph in Medieval Studies. Her recent research on architectural psychoacoustics of Hagia Sophia is in collaboration with Jonathan Abel (Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics) and was awarded the Presidential Fund for Innovation in the Humanities and two grants from Stanford Institute for Creativity and the Arts (learn more here). Pentcheva has held fellowships from Mellon New Directions, Alexander von Humboldt, Dumbarton Oaks, and the Onassis Foundation. In 2007 she taught a graduate seminar on Phenomenology of the Byzantine Icon at the Kunsthistorisches Institut, Florence.

Rossitza Schroeder is Assistant Professor of Art and Religion at the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley. She works and publishes on Byzantine monastic arts, Italo-Byzantine cultural exchange, and heritage studies. Schroeder has held fellowships at the American School of Classical Studies, Dumbarton Oaks, and the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies at Princeton University.